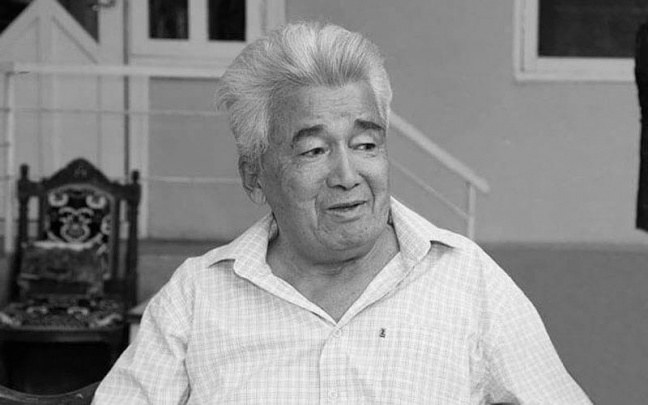

From anthem to exile: Family recalls Abdulla Oripov’s struggles and legacy

March 21 marked the 84th anniversary of the birth of Abdulla Oripov, Uzbekistan’s People’s Poet, author of the national anthem, and a towering figure in national literature. A Kun.uz correspondent visited the poet’s home, speaking with his wife, Hanifa Mustafoyeva, and daughter, Shoira Oripova. In the interview, they reflected on the final days of Oripov’s life, his creative and political endeavors, and shared personal memories.

According to Hanifa Mustafoyeva, Oripov lived with the people’s burdens on his shoulders, rarely experiencing a carefree day, his life consumed by relentless thought:

“I can’t recall a single day when he was at peace — he worried about everything and lived a restless life. Family never came first for him; his thoughts were always with the people.

“Our wedding took place in 1967 when I was just 17; we hadn’t even formalized it officially. Many creatives from Tashkent — Shukur Kholmirzayev, Nizom Komilov, Tulqin, and others — attended. During the celebration, Abdulla-aka recited a ghazal by Erkin Vohidov and his own poem “Yozajakman” (I’ll Write). Afterward, those very poems led to prolonged interrogations. In his own words, ‘eight lines of poetry rained down on me like eight bombs.’ Even small works like “Tilla baliqcha” (Golden Fish) and “Dorboz” (Tightrope Walker) were given political undertones, subjecting him to constant pressure,” she recalls.

Hanifa Mustafoyeva notes that after the death of writer Abdulla Qahhor in 1968, creatives tied to his literary school faced increased scrutiny and inspections, with Oripov no exception:

“After Abdulla Qahhor’s passing, they frequently investigated Abdulla-aka as his disciple. I vividly remember his later laments: ‘Only my dreams remain untouched by the overseers,’ and ‘Someone’s neglecting their own work to measure my every step,’ he’d sigh. He keenly sensed the situation — you can see it in his poetry if you read it,” she says.

Under the Soviet regime, every work faced strict censorship, according to his wife. Even Oripov’s poem “Onajon” (Dear Mother), written for his late mother, struggled to see print. When it finally appeared in “Saodat” magazine years later, it had undergone significant alterations:

“I came to Tashkent in 1968 and began observing Abdulla-aka’s life closely. That year, his mother passed away, and he always carried “Onajon” (Dear Mother) in his pocket. When it was finally published, he said with a hint of despair, ‘I got it out at last.’ Even a poem about a mother was hard to get printed. We had a home phone, and they’d call constantly — ‘Change this word, adjust that part’ — until half the lines were rewritten by the time it reached the press,” Hanifa Mustafoyeva recounts.

In 1988-1989, the Uzbek language was sidelined, university Uzbek language departments were shut down, and Navruz celebrations were banned. During this time, a prominent article titled “Salom Bahor!” (Hello, Spring!) appeared in a newspaper under Oripov’s name, though, as his wife reveals, he didn’t write it:

“In reality, my husband didn’t pen that article. They summoned him and forced him to claim authorship. Saying ‘no’ wasn’t an option — resistance meant not just personal ruin but pressure on your loved ones too. Abdulla-aka had three brothers and feared that defying the system would lead to their exile. Our children were still young, but he worried more about his siblings than his own family. ‘I could bear it myself, but they’d flatten my kin too,’ he’d say, forced into silence. They left him no choice but to comply.

“There were times when dirt was thrown into pots of boiling sumalak during Navruz — such incidents tore at his soul. He wrote four lines about Navruz:

Forgive us, dear Navruz, we plead,

Our eyes were dimmed by careless heed.

Your cheek we scarred with thoughtless blow,

Now briny balm salts our woe.

“His anguish shines through those lines. Even circumcision ceremonies were forbidden back then. Abdulla-aka dreamed of holding one for our son, but permission was denied. ‘If you hold this event, they’ll expel you from the Party,’ they warned. So, he sent me and our son Ilhomjon to the village, saying, ‘My brother’s holding a ceremony for his son — take ours and have them circumcised together.’ In those final years, even funeral prayers were banned; the deceased were buried with speeches and music,” his wife recalls.

Hanifa Mustafoyeva credits Sharof Rashidov, Uzbekistan’s leader at the time, with protecting the creative community as much as possible. She believes Rashidov played a key role in getting Oripov’s poems published in Moscow:

“I’d tease him, ‘They haven’t dragged you to Hadra and shot you for these poems yet?’ His verses do have bold, sharp edges. Sharof Rashidov, being a literary man himself, perhaps shielded my husband during dangerous times, voicing through him the pains he couldn’t express. He turned a blind eye to much and offered support.

“Beyond poetry, Abdulla-aka became a political figure. In 1989, he served as a USSR deputy, attending Gorbachev’s government sessions. He joined our first president, Islam Karimov, in declaring Uzbekistan’s independence. Heading to that meeting, he stayed up all night writing a poem to recite in the hall. “Independence wasn’t yet certain, but with hope, he prepared those verses. He always said, ‘A poet without a fresh draft in his pocket is no poet at all.’”

“For the national anthem competition, Oripov submitted entries under the pseudonym “Qungirtovliq.” The selection spanned three stages over nearly two years, with his poems consistently ranking high. After tireless effort, he wrote two versions, ultimately submitting the one beginning, “My country, sunny and free, salvation to your people.” The anthem’s original Soviet-era music remained unchanged, polished to fit his words. “Mutal Burhonov came to our house daily, playing the tune on the piano, singing it with our children to ensure every word aligned with the melody. The anthem’s text was heavily revised — I’ve donated several versions to museums, and we still have 50-60 drafts at home,” Hanifa Mustafoyeva says.

Oripov’s daughter, Shoira Abdullayeva, recalls her father’s connection to the anthem:

“Every New Year, he’d eagerly await the anthem’s broadcast. Friends and students would jokingly say, ‘Heard they’re changing the anthem,’ upsetting him. From mid-year, he’d count down six months to New Year’s. When it played unchanged, he’d tear up, saying, ‘Thank goodness, they didn’t alter it.’”

In his final seven years, Hanifa says, Oripov lived in near house arrest, shunned by peers and students:

“In his last days, he’d say, ‘Don’t come near me — if you do, my shadow will taint you. Pushing you away is my kindness.’ The press, TV, radio — all cut him off. Yet he never blamed Islam Karimov, sensing other forces at play.”

Despite health struggles, Oripov never stopped creating. His condition worsened in the fall of 2016, leading to treatment in the U.S. Hanifa recalls his longing for Uzbekistan, a sentiment he repeated until his final moments.

Abdulla Oripov passed away on November 5, 2016, in Houston, USA. His body was returned to Uzbekistan and buried in Tashkent on November 10.

“My father wished to be laid to rest beside his parents in Nekuz village, Kashkadarya region, at the Toyloq Ota cemetery. But as a public figure, and considering many couldn’t travel there, the government arranged his burial at Tashkent’s Chigatoy cemetery,” says Shoira Oripova.

Recommended

List of streets and intersections being repaired in Tashkent published

SOCIETY | 19:12 / 16.05.2024

Uzbekistan's flag flies high on Oceania's tallest volcano

SOCIETY | 17:54 / 15.05.2024

New tariffs to be introduced in Tashkent public transport

SOCIETY | 14:55 / 05.05.2023

Onix and Tracker cars withdrawn from sale

BUSINESS | 10:20 / 05.05.2023

Latest news

-

Uzbekistan’s permanent population nears 38 million

SOCIETY | 20:08 / 08.07.2025

-

Mirziyoyev and Putin discuss further strengthening trade and economic ties

POLITICS | 20:05 / 08.07.2025

-

Uzbekistan showcases digital progress and media reform at WSIS+20

SOCIETY | 19:13 / 08.07.2025

-

IELTS in Uzbekistan temporarily shifts to computer-only format after suspected answer leaks in paper-based tests

SOCIETY | 19:11 / 08.07.2025